At some future point,

But even though Christians are unanimous in our belief “from [heaven] he will come to judge the living and the dead,” we’re not universal as to how it’ll happen. Jesus didn’t give us specifics. He gave us

Acts 1.7 KWL - Jesus told them, “It’s not for you to know times or timing.

- That, the Father sets by his own free will.”

The Father doesn’t set it by anything we do, and certainly not our timelines of End Times events. We have to trust him to be in charge of it, and let things unfold as God chooses.

Since Christians aren’t agreed as to how the End comes, most of us agree to disagree. Most. Some of us are absolutely certain it’ll only happen the way we say it will, and have declared war on any Christian who teaches otherwise. I know I’ve certainly been called heretic by some of ’em. Sure glad those folks aren’t in charge of what’s orthodox and what isn’t.

But as far as End Times interpretations are concerned, there are four major camps we Christians fall into. So I thought I’d introduce you to them. Yes, I’ll admit upfront I fall into the preterist camp. But again, you’re not heretic if you go for one of the other views. Wrong probably, but not heretic.

End of Days.

The most popular and common view is the

- Evil starts to gather its forces for one big final showdown between them and Christ. Plagues, pestilence, horsemen of the Apocalypse, the Beast, etc.

- Good people try to fight off evil… and lose. (Because evil’s just so powerful.)

- Jesus returns and instantly wipes out the Beast and its forces. (Because as powerful as evil might be, Jesus is almighty.)

- It’s the end of the world. Planet goes foom. Either it’s annihilated in the force of Jesus’s return, or he snaps his fingers and makes it go away. Gone.

- The righteous suddenly find themselves in heaven, where they’ll live forever.

You’ll notice there’s a lot of End Times imagery missing from this scenario. Where’s

It’s because the End of Days is based on the idea all the apocalyptic visionary stuff is happening behind the scenes. They don’t play out in our human history; they happen in angelic history, in heavenly history. They represent the major events of the angelic war which has been going on since creation. But they don’t have a lot to do with us. We’re minor figures in the cosmic plan, so we don’t see these events play out. We just go straight to heaven.

The whole point of this view is heaven. Apparently all this time when people died, they didn’t

Yeah, very few of these ideas come directly from bible. They come indirectly, through folk Christianity and Christian myths. They’re guesses about the End, made by people who figured Revelation is too confusing, so they skipped it and created an End Times view which puts ’em straight into heaven. Not even New Heaven.

So to these folks, any world-ending event might mean the End of Days. A pandemic, an extinction-level meteorite, a global thermonuclear war,

As you can tell, this scenario really doesn’t even need God to get involved. It’s probably why so many

Utopia.

The word

- Humans decide to stop fighting and scratching and biting one another, and work together, under God, for the good of the world.

- We unify our economies, unify our governments, pass laws eliminating bloodshed and poverty and promoting peace and harmony, and people actually follow these laws instead of trying to create loopholes for themselves.

- We live in comfort and ease, solving every new problem we come across with grace and generosity. What a beautiful world this will be; what a glorious time to be free.

- Jesus, seeing we’ve finally achieved the kingdom he wanted for us, returns to personally reign over us all.

No tribulation, ’cause the pre-utopian times count as tribulation. The Beast and its minions were defeated back when we finally got serious about sorting out the world’s problems. It’s definitely a postmillennial perspective. And it sounds an awful lot like Star Trek… which stands to reason.

Utopianism and utopian science fiction like Star Trek are based on

After two world wars, the utopian view fell out of fashion. Germany used to be considered one of the more “enlightened” civilizations in the world, and attempted to create a thousand-year kingdom on earth… but turns out they were led by

There’s still a lot of modernism in American Christianity though. Our conservatives love to claim we were founded as a Christian nation, as a special and chosen people, by God-fearing founding fathers; and if we just returned to biblical standards and principles, we could fix our nation’s problems and turn the United States into God’s kingdom. And y’know, even Christians who don’t believe in utopianism fall for this rhetoric on a regular basis. It just sounds so patriotic… and blind to the fact Germany tried the very same thing, and look where they went. All it takes is

Nope; Jesus has got to rule his kingdom personally. Unregenerate humans can’t. And once Jesus conquers the world, he’s overthrowing every government. Including ours. No matter how “Christian” we make it appear.

Darbyism.

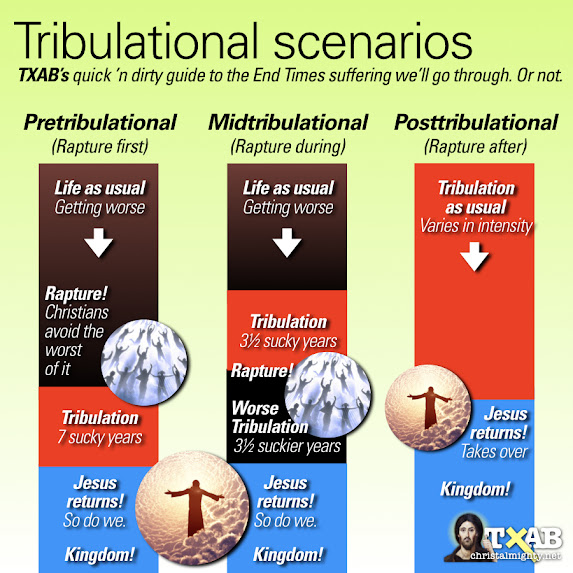

Whenever an End Times scenario claims there’s a rapture separate from Jesus’s return, whether it happens before or during tribulation, we’re talking Darbyism.

John Nelson Darby believed

Okay, if God turned off the miracles, what about the End Times? The apocalypses make it sound like it’s full of miracles. Darby’s solution was

Goes like so.

- The world’s Christians (the real Christians, anyway) unexpectedly vanish in the rapture.

- The Beast takes over the world, promising peace and security, and actually creates peace in the middle east for once. But halfway through the seven years, the Beast breaks the peace to go to war with Israel—whom God miraculously defends.

- Various plagues and disasters meanwhile smite the world and its wicked.

- The Beast attempts one big final battle… and Jesus invades, destroying the Beast and its armies.

- Jesus, his Christians, and Israel take over the world, and run it for a thousand years.

- Satan tries to raise one more battle, but Jesus easily wins. Then Jesus raises everybody from the dead, judges the world, throws the wicked into hell, and replaces earth with New Earth.

Because Darbyists tend to be very detailed—they claim to know the exact sequence of events during the End Times—they appeal anyone who desperately wants to know about the End. Even if they believe they’ll be raptured out first.

But since no two Darbyists believe precisely alike, each must publicize their own specific views. Hence Darbyists write End Times books like you wouldn’t believe. Go to any Christian bookstore and they dominate the shelf. They have “prophecy conferences” galore, where you can go listen to a bunch of of ’em unroll their timelines and tell you how it plays out. Look up End Times on the internet and nearly all the sites are of the Darbyist persuasion. They even have study bibles, which’ll show you just

Like I state in my New World Coming articles, they’re all wet. I grew up in churches which are totally into their view, which is why I know it so well. But I hang my hat on the preterist view.

Preterism.

Jesus told his students about the End, but primarily about the near future. That future came and went. The great tribulation already happened. The bulk of those prophecies came to pass in our past. It’s history now. The only thing left,

Not “partial preterism.” A

Nor “full preterism.” That’s what we call people who claim Jesus already has returned, and is ruling the world. (If so, he’s really bungling it!) You gotta either be nuts, or have some really distorted views on God, to think Jesus has returned already.

But properly, preterists recognize the only thing we have left to look forward to is the soon, unexpected, and rapid return of Christ Jesus. The skies roll back, the trumpet blasts, the angel shouts, the Lord descends, every Christian (dead and alive) gets transformed, joins him in the air, and the billions of us proceed to Jerusalem where he takes over the world. It’s gonna freak out everyone. But it’s gonna be awesome.

The great tribulation? Happened in the year 70, when the Romans destroyed Jerusalem. Regular tribulation is the usual state of Christianity; Christians are still the most persecuted religion in the world, and only comfortable, safe Christians in the United States are under the delusion it’s the circumstances of a different dispensation. The Beast? There’ve been a bunch of power-mad world leaders who are decent candidates for the Beast. And so on. Go through all the other prophecies in the bible: Either they’re done—or they don’t have to be done till Jesus returns. Like all Israel getting saved. Once their Messiah arrives, he’ll sort them out. Till then, keep doing as we’re doing: Share him with them. ’Cause we’d all prefer they rejoice at his return, not freak out like the pagans.

Nope, nothing more has to happen first. ’Cause they’ve happened already. They’ve had 20 centuries to happen. You can figure out when they happened, assuming you didn’t skim that part of your history classes. Or if you haven’t already assumed, as the Darbyists teach, that those events can’t be fulfillments, ’cause futurism. But only Jesus happens in the future. Everything else got out of his way.

Some preterists call ourselves

Yeah, there are other theories.

I went through the main four theories, which you’ll find among most Christians; probably 99 percent of us. There are of course others. In fact, you might be one of those exceptions, grousing, “You didn’t cover my view.” No, I didn’t.

But I will cover this fifth one:

“I’m a pan-millennialist,” a Christian of my acquaintance liked to joke. “I believe it’ll all pan out in the end.” A lot of Christians, fed up with “prophecy scholars” who know nothing about either prophecy or scholarship, have decided this is precisely the way to go. My panmillennialist acquaintance didn’t wanna get into End Times squabbles. He didn’t care which came first, the chicken or the Beast. He just figured Jesus would come for him someday, and he was fine with that.

And of course Jesus will. The reason we Christians fret about the End Times (“What’s gonna happen?” “Who’s the Beast?” “Must stop the one-world government!” “Must fight the New World Order!” “They’re out to kill us all!”) is fear. Since knowledge is power, we figure if we get a little End Times knowledge, maybe we can have some control over our future. But here’s the reality: We have no such control.

Jesus holds the keys to death and hades,

What we do get to know is that in the End, God wins. Jesus reigns. We live again, and live forever. No more tears and sorrow. Evil is dealt with. Faith is rewarded. Let it be enough.

And if anyone, anyone teaches it’s okay to suspend God’s commands because the End is coming—if anyone values their own life above God’s kingdom, if anyone values their own interpretations over God’s grace and power, and if anyone tries to exploit human fears for fun and profit—they’re wrong. Don’t let fear become a justification for evil. Those behaviors put us outside God’s kingdom,