I grew up Christian. And Fundamentalist, so one of the things they frequently told us was Jesus is returning. Awesome!

Except… well, kinda not. Because while it was gonna be great for us Christians, who’d get raptured away before the world began to suck—okay, it already sucks, but the idea is it’s gonna suck way, way, WAY worse—things are gonna get way, way, WAY worse. If any of us don’t qualify for getting raptured, we’ll have to live through it. If anyone becomes Christian after the rapture takes place, they’ll have to live through it too. That’s the whole premise of the Left Behind novels, y’know—people who got “left behind,” and now have to suffer through campy villains and the worst kind of melodrama. Oh yeah, and great tribulation.

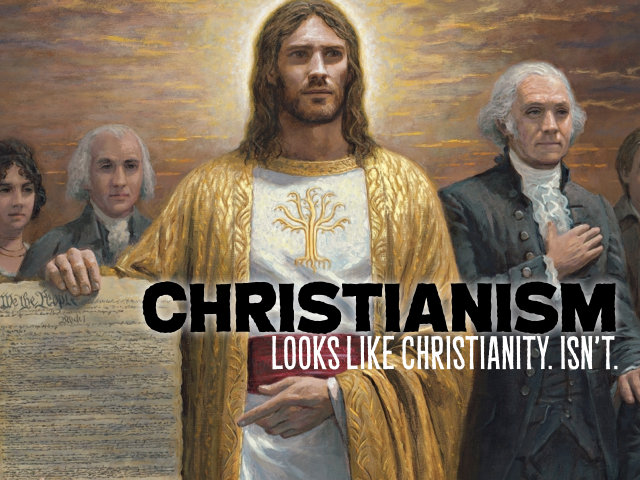

Kids get really anxious about this sort of thing. Adults too, which is why my church went on and on about it. Some churches preach about little else. I got a coworker who constantly asks me what I think about the End Times. He’s got fears. ’Cause his church has fears, and put ’em into him. Tons of Christians have fears… and you realize it drives their politics. It’s why so many Americans are desperately afraid of anything which might trigger the End Times.

Wait, but the rapture and the second coming are part of it, right? Don’t we look forward to that? Again yes… and well, kinda not. The way dark Christians get about the End Times, people’s fears about it outweigh any potential joy they’d have in Jesus’s return. Even as their preachers try to say, “No no no; the second coming’s gonna be amazing!” they still spend more time, more emphasis, on the terrors and suffering to come, and lay on the stick so hard you forget there’s any carrot. It’s messed up, but that’s dark Christianity for ya.

So I had lots of questions about the End Times. ’Cause I read Revelation, which is all about the End, and I couldn’t make heads or tails of it. (’Twas a combination of the apocalypses and the obscure vocabulary of the King James Version. They made things nice and cloudy.) I went to Mom, but she was a relatively new Christian and didn’t have any answers either.

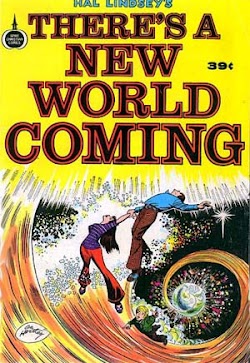

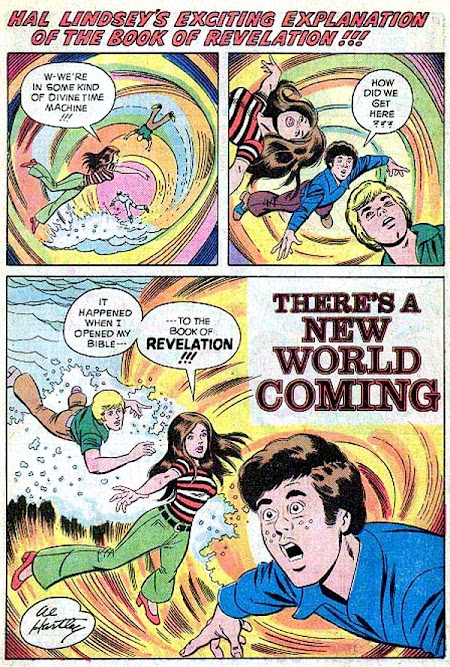

But then she found me a comic book which claimed to spell out everything.

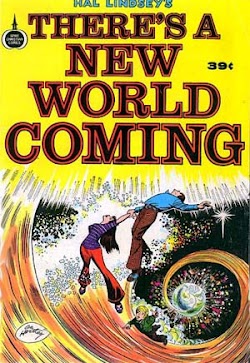

Al Hartley’s There’s a New World Coming, based on the book by Hal Lindsey.

And now I’m gonna inflict share this comic book with you. It’s Al Hartley’s comic book adaptation of Hal Lindsey’s 1973 book There’s a New World Coming: An In-Depth Analysis of the Book of Revelation. Which itself is his update to his 1970 bestseller The Late, Great Planet Earth. (’Cause he had to update it, ’cause some of his predictions in the previous book weren’t happening the way he claimed they would. But I’ll talk about Lindsey another time.)

Between this comic book, and an in-depth Sunday school class on the End Times which I later took as a teenager, I was thoroughly introduced to the Darbyist spin on the End Times. I call it Darbyism after John Nelson Darby, the guy who came up with his particular system of dispensationalism.

Darbyists tend to call themselves “premillennial dispensationalists.” They believe in Darby’s view of dispensationalism—that God used different systems of salvation throughout human history, and that during Old Testament times people were no-fooling saved by their works. Not anymore; we’re saved by grace now. This distinction is the only thing keeping Darbyism from being full-on heresy—although you’ll find a number of Darbyists now think they’re saved by believing all the correct things, and those of us who don’t believe in Darbyism might wind up getting left behind. Yikes.

Anyway Darbyists are the ones who write the bulk of the End Times books in the Christian bookstores. They’ve spent a lot of time “discerning the news” and deducing which of it lines up with End Times prophecy, then publishing their findings. There’s good money in it! But no I’m not claiming they’re trying to make a quick buck off paranoid people: They themselves are paranoid, so they think they’re doing Christendom a service by warning us what’s coming. Even though, time and again, they’re proven wrong. But maybe, just maybe, this time they’re right… and so they write another book. And we let ’em, instead of stoning them to death. ’Cause grace.

Let’s dive into the book already, shall we?

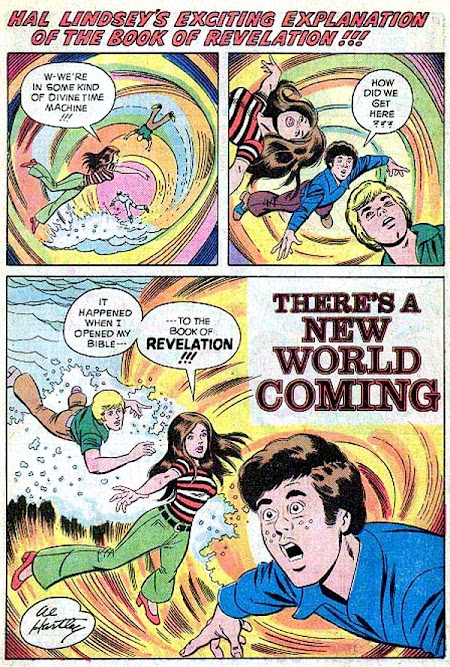

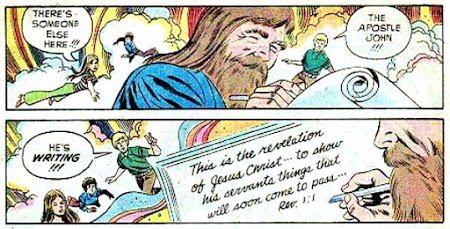

The comic book begins with three kids from the 1970s, who weren’t at all fiddling around with LSD. Really. They just opened up their bible and were suddenly sucked into a psychedelic vortex. For totally innocent reasons. Promise.

This is why you don’t lick Revelation’s pages, kids. TNWC 1

Wonder whether Superbook pays Hartley’s estate any residuals for swiping his idea. They’d better.

The kids never get named. So for convenience I’ll call ’em Archie, Jughead, and Betty.

| ARCHIE would be the blond boy, who looks kinda like Freddy from Scooby-Doo. He’s the know-it-all of the book. |

| JUGHEAD is the stock dumb guy, the fearful character who doesn’t know a thing, so the know-it-all has to explain everything to him. Comes in handy for those readers who don’t know anything either. |

| BETTY is the token girl. We get the idea she probably knows as much as Archie—maybe even more!—but since she’s a girl she’s gotta stay silent. Fundies, y’know. |

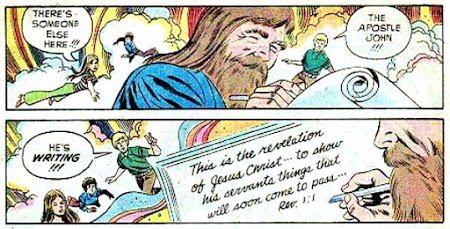

The kids aren’t alone in the vortex. The guy who wrote Revelation is in there with them.

Hey look, it’s Gimli from Lord of the Rings. TNWC 2

For some reason he’s ruddy as a Scotsman; not at all as middle eastern as one should expect. And he’s writing Revelation in English, not ancient Greek. But it’s not even King James Version English, which’d be the mandatory translation of most every Darbyist. Betcha most of them found that the most bothersome thing in this comic book.

Betty comments, “When you see the mess the world is in… it’s hard to believe that Christ is in control of things!” Archie reassures her, “…But history is moving precisely as he predicted!”—and then we’re introduced to how Darbyists claim Jesus predicted things: The End Times Timeline.

Let me make this perfectly clear: To a Darbyist, the End Times Timeline is canon. Do not mess with it.

What Darbyists figure is the divinely-inspired End Times Timeline. TNWC 2

It’s even more sacred than bible, because it’s the lens through which they interpret it. But despite what they claim, it’s not actually based on the bible. It’s based on dispensationalism.

The End Times Timeline posits a future seven-year period, based on various scriptures which refer to various seven-day, seven-week, or seven-year stretches. In it, every single End Times prophecy gets fulfilled in a bloody frenzy. Lots of chaos, war, disaster, destruction. Tribulation, they call it. Those who trust Christ before tribulation, are spared it all. Anyone who misses the pretrib rapture, who realizes “Aw crap; the Christians were right!” and repents, is nonetheless just as screwed as the pagans. Now they gotta ride out tribulation, and be part of all the End Times prophecies about Christians getting persecuted. Meanwhile the other 2 billion of us lounge around in heaven.

Well… Darbyists are pretty sure it’ll be substantially less than 2 billion. Like the scripture says, “Two in a field—one taken, one left.” So it’ll be more like 1 billion. Or fewer. But let’s not get into that today.

God has HAD IT with these motherf---ing pagans. TNWC 3

For those who can’t fathom why a loving, patient, gracious God would suddenly get all medieval on humanity’s ass, Darbyists usually claim it’s because he is loving and patient. The tribulation is just tough love. Really tough love. Big bowls of angry, violent, genocidal love.

They spin it as one very last chance for everybody to repent before Jesus officially returns. ’Cause once he returns, he’s sending the wicked straight to hell. He’s not gonna let them experience his kingdom, where he rules the world and they get to experience his love and grace firsthand. He’s gonna have them experience his wrath, and that has to win them over. Kindness and gentleness didn’t work, so let’s try rage.

No, it’s not consistent with God’s character whatsoever. But Darbyists are dispensationalists, remember? They believe God practiced multiple methods of salvation, and didn’t always save by grace. In Old Testament times, people had to follow the Law or they’d go to hell. And in each different dispensation, God actually demonstrates a different character. It’s why God comes across all pissed off and smitey in the OT, but mushy and forgiving in our dispensation of grace. And during the End Times, it’s kinda like God goes back to rage, Old Testament style. Not towards us Christians; we’re up in heaven with him. But the pagans? They’re royally screwed.

The Darbyist philosophy of the End.

John Nelson Darby’s three other philosophies get jumbled together with his worldview, and therefore his interpretation of the End: Futurism, cessationism, and escapism.

FUTURISM is the belief every End Times prophecy takes place in future. Not just the future of Jesus and the bible’s authors: Our future too. Jesus’s prediction of the temple’s destruction Mk 13.2, Mt 24.2, Lk 21.6 was fulfilled in the year 70, when the Romans invaded and razed Jerusalem. But Darbyists claim no it wasn’t. It’s yet to come. Because immediately after Jesus foretold Jerusalem’s demolition, he said this:

- Mark 13.24-27 KWL

- 24 “But in its time, after that tribulation:

- ‘The sun will go dark. The moon won’t give its light.’ Is 13.10

- 25 The stars will fall down from the sky.

- The powers in the skies will be shaken.

- 26 Then the Son of Man will be seen, arriving in the clouds with great power and glory.

- 27 Then he’ll send out the angels.

- They’ll gather together his chosen people from the four winds,

- from the edge of the world to the edge of the sky.”

And if Jesus’s second coming is part of the great tribulation prophecy—as they insist it is—then it can’t’ve happened in 70. It must therefore happen during the End Times.

This is how they treat every prophecy about the End. Or every prophecy which might be about the End. They figure if a prophecy, whether in the Old Testament or New, hasn’t yet been fulfilled as far as they can tell, it will be—at the End. Since few of them know squat about the ancient Middle East, they believe a lot of prophecies aren’t yet fulfilled. So they find a way to shoehorn ’em into the End Times Timeline. And this is why they believe a lot of things will happen at the End, which are nowhere to be found in Revelation.

Why can’t these prophecies have been fulfilled during the past 20 centuries? Mainly ’cause cessationism.

CESSATIONISM is the belief God stopped doing miracles once the bible was completed. No, not every Darbyist is cessationist. But John Nelson Darby absolutely was, and the reason he came up with his system was so he could explain why miracles happened in bible times but, supposedly, not today.

And the reason Darbyism is futurist, is because in order for every prophecy to happen, God has to turn the miracles back on. And he won’t till the End. So they can’t have happened in the past 20 centuries of Christian history. It’s physically impossible.

I’m Pentecostal, and know plenty of Pentecostals and continuationists who recognize God never did turn off his miracles. Yet they totally believe in Darbyist versions of the End Times. It’s because they don’t know the underlying, faithless philosophy behind the system. It’s because they grew up in churches which assumed the Darybists were right. Or, when they had questions about the End Times, they were given Darbyist literature, same as I was, and assumed these guys know what they’re talking about. They never investigated further; never even thought to. They have no idea its futurism is based on unbelief—heck, in a deliberate rejection of God’s present-day power.

Anyway, if all the End Times prophecies can’t be fulfilled yet, they’re in our future. Which means Jesus can’t return till they happen. Which means Jesus’s return is constantly pushed forward in time. They don’t believe he can return till specific events first happen. In reality absolutely nothing can prevent Jesus from returning. It’s why he’s told us to stay awake—he can return at any time! Mk 13.33-37 Stop figuring he can’t come back till the Darbyist checklist of End Times events gets marked off. The only thing hindering Christ is he wants to save everybody he can before he returns. 2Pe 3.9 That’s all.

ESCAPISM, last of all, is the idea we Christians get to escape all the bad stuff. Jesus is gonna rapture out us Christians before we might really suffer. Darbyists claim it’s why Jesus taught “Two in a field—one taken, one left.” Mt 24.40 It’s not about the Romans killing half the Jews in the world; it’s about Jesus abandoning half the people who assume they’re Christian, ’cause half of us don’t really believe in him. So the left-behind half get smited along with the wicked.

Are these views taught in the bible? Nah. They first have to be overlaid upon the bible. That’s why when you read Revelation you’re not gonna see any of this. It’s why you first have to buy Darbyist books, so they can explain how to read Revelation and the rest of the bible through their lenses. And once they put these lenses on, a lot of Darbyists seriously struggle to take ’em off. I’ve pointed out more than once how 1 Thessalonians 4.16-17 clearly describe the rapture and the second coming as one and the same event, and Darbyists read these verses and simply can’t see it. Their End Times Timeline takes priority over bible, and their lenses have turned into blinders.

The pretrib rapture.

The End Times Timeline always begins with the rapture, so that’s where the book goes next.

The great what now? TNWC 3

I had never, ever, never ever heard of the rapture referred to as “the Great Snatch.” Never before this comic book. Rarely since—and only because people keep referring to this illustration, and making fun of it. I’ve definitely heard the term “great snatch” before, but it means something entirely different. Go ahead and Google it, though the results may horrify you.

Why’s it used here? Bear with me; I got a theory.

Back in the 1950s and ’60s, the Comics Code Authority censored all the comic books to a G-rated level. But comic book artists would occasionally try to slip a naughty joke past the censors. Like when Batman and Robin would talk about having a “gay old time” beating up criminals. Like when the Joker tricked Batman into making a mistake, and wouldn’t stop calling it Batman’s “boner”… way too often. So much, you had to wonder, “Don’t the writers realize 12-year-old boys read this stuff? How do you think their adolescent minds are gonna handle this material” Um… the writers totally knew. That’s why they slipped those jokes in the books. They shared that adolescent sense of humor.

So did Hartley, or one of the folks at Spire Comics, slip a naughty joke into a Christian comic book? Yes. Yes they did.

Why? Probably because one of ’em didn’t entirely buy Hal Lindsey’s worldview.

Many’s the time I, while working for one Christian ministry or another, was obligated to publicize some Christian nutjob. Still happens. Might be some conspiracy theorist, some preacher who never quoted the bible in context, some dangerously undereducated youth pastor, some false prophets who were trying to spread their fame instead of the gospel. I don’t agree with these loons, but my job isn’t to publicly correct their rotten theology. It’s to do as my boss or pastor instructs, and make the publicity packet, design the ads, or introduce the cranks to the audience. I gotta resist my strong temptation to voice my disapproval—or undermine ’em by picking the least-flattering publicity photo. (Although some of them do that job for me by submitting some of the cheesiest, vainest, Glamour Shots style pics. Creates a little halo effect around the comb-over.) I must resist the temptation to give ’em backhanded compliments, or kick the legs out from under their sermon by pre-correcting their out-of-context verses or inaccurate teachings in my introduction. You know, the usual passive-aggressive tricks.

So somebody at Spire Comics must’ve believed Lindsey’s version of the rapture is all wet, and therefore titled it “the Great Snatch.” Or tricked Hartley into calling it that. And if you poke around the internet, you’ll find a lot of people, pagans and Christians alike, find this description hilarious. It’s the fastest way to mock the rapture as too stupid to take seriously.

How Darbyists imagine the rapture varies. In Left Behind, Tim LaHaye described the Christians as simply vanishing, leaving behind absolutely everything: Clothes, jewelry, artificial hips and knees, pacemakers—as if God wants nothing non-biological. Off they went, to appear in heaven before God… buck naked, missing prosthetic limbs, suffering giant heart attacks.

Now, read about Jesus’s rapture in Acts, which the two men in white (probably angels) said would resemble his second coming. Ac 1.11 And oughta resemble our rapture. Jesus didn’t vanish and leave his clothes behind. He bodily, visibly went up into the air. It’s not gonna be a secret rapture, like some Darbyists describe it. The comic book version is much closer to what might look like—minus the ’70s fashions.

When God turns on the heavenly vacuum cleaner. TNWC 4

In Hartley’s version, at least we’re clothed. But the one thing Darbyists are consistent on is the rapture is unexpected. There’s no parting clouds, no trumpet, no falling stars, no sky going black, nothing. The planet’s Christians whoosh away without warning. Drivers disappear from their cars, which’ll then slam into things, like pedestrians and puppies. Hence the popular “In case of rapture” bumper stickers.

It’s not what either Jesus or the the apostles told us. Here’s how Paul, Silas, and Timothy described Jesus’s second coming to the Thessalonians.

- 1 Thessalonians 4.13-18 KWL

- 13 Christians, we don’t want you to know nothing about those who are “sleeping”:

- You ought not grieve like all the others who have no hope,

- 14 for if we believe Jesus died and rose,

- likewise God, through Jesus, will bring our “sleepers” with him.

- 15 We tell you this message from the Master.

- We who are still alive at the Master’s second coming don’t go ahead of those who’ve died.

- 16 With a commanding shout, with the head angel’s voice, with God’s trumpet,

- the Master himself will come down from heaven.

- The Christian dead will be resurrected first.

- 17 Then, we who are left, who are still alive,

- will be raptured together with them into the clouds,

- to meet the Master in the air.

- Thus, we’ll be with the Master—always.

- 18 So encourage one another with these words!

Now, compare this with the End Times Timeline:

Green arrow: Rapture. Yellow arrow: Jesus’s return. TNWC 2

The apostles described the rapture as the Master’s coming. 1Th 4.15 They didn’t do so ambiguously. It’s right there in the text, plain as day. But Darbyists claim the second coming and the rapture are years apart. They’re not simultaneous. There’s a seven-year tribulation in between.

What basis do they have for saying so? ’Tain’t bible. There are no other passages in the bible about the rapture. Jesus’s return comes up plenty of times, but Christians going to meet him in the air: 1 Thessalonians 4.13-18 is all we got. (It’s why some Christians wonder whether there’ll even be a rapture: They want at least two proof-texts before they’ll declare a doctrine solid. Otherwise they say it’s debatable. I don’t agree, but that’s me.)

Most Darbyists figure in order for evil to run rampant on the earth, the Holy Spirit, who’s holding back the evil, has to be “taken out of the way.” 2Th 2.7 And since the Holy Spirit lives inside every Christian, he’s not leaving without us. So he takes us with him to heaven. Then evil can run amok. More so than usual.

What about the Christians who’ll be persecuted during the End?—the protagonists of Darbyist novels and movies, whom they imagine will be left-behind pagans who repent after the rapture. If there’s no Holy Spirit, how can anyone become Christian? It’s impossible. Well, Darbyists have explained to me, the “Christians leave because the Spirit leaves” idea is just a theory. A guess as to why there’s a pretrib rapture. We don’t really know the Spirit will leave, ’cause he’s gotta stick around to make tribulation saints. But just the same, there is a pretrib rapture. Bible says so.

No it doesn’t, but good luck cutting through that thick fog of illogic and denial. You can’t eat your cake and have it—or in this case, rapture your Spirit, then have him sneak back to make new Christians for your End Times novel.

There’s no biblical precedent for escapism either. Noah may not have drowned in the great flood, but he did have to build an ark and ride it out. The Hebrews weren’t smited by the Egyptian plagues, but they were still in Egypt, watching. Passed over, when the LORD’s angel killed the Egyptians’ kids, but still there. When foes came to destroy Israel, and God destroyed the foes first, the Israelis were there, all ready for battle, but sitting it out as God worked. He didn’t rapture them away to a place of safety. He’s their safety. As he is ours.

The point of the rapture isn’t escape, but to join the invasion on our Lord Jesus’s side. He’s coming down. He’s not going back up for another seven years, then coming back for a third coming. Think of it like an ordinary military invasion: When the invading army rolls into town, all the agents in-country, the people who’ve been laying the groundwork for the invasion, quickly come out of their hidey-holes and join the troops. That’s what we’re doing at the rapture: We’re falling in behind the general. We don’t go into the air to stay in the air. We join him in the air—so when he touches down on earth, it’s with his full complement of 2 billion immortal Christians. Picture that.

Gotta admit: I really like the idea of getting taken away before the bad stuff happens. Martyrdom’s gonna suck. But if that’s so, what was the point of Jesus warning us that life is suffering? That he’s gonna reward those of us who hold out till the very end? He promises this in Revelation, of all places. Rv 2.25-26, 3.11 But most Darbyists insist the rapture takes place before anything in Revelation happens. Doesn’t matter that St. John’s depicted in the vortex with the kids—as Hartley reminds us—

You think he dyes his hair? I think he dyes his hair. TNWC 5

—still writing the introduction, for we’re not even in his book yet.

In fact, since I’ll stop here, we’re not even gonna get to the book of Revelation. That’s just how screwy the End Times Timeline is.