- WORLDVIEW

'wərld.vju noun. A particular philosophy about life, or concept of human and social interaction.

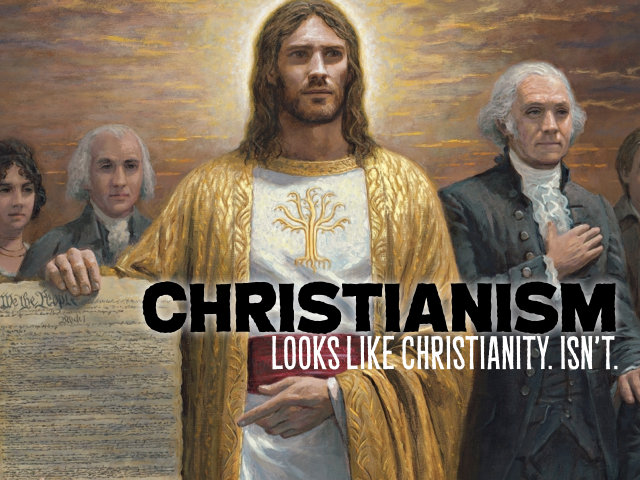

When Christians talk about worldviews, we’re talking about politics.

Yeah,

- It invariably leads to a politically conservative point of view—regardless of whether Jesus even addressed, much less supports, their favorite conservative views.

- It invariably leads to their particular church’s views on God. Fits extremely well if you’re

Calvinist orFundamentalist … and less so if you’re not. (God help you if you’reRoman Catholic. ) - It doesn’t promote loving our neighbors so we can point ’em to Jesus. More like being appalled at the stuff they’re trying to sneak past us, and therefore

angry with our neighbors.

Our word

Historians and psychologists were more fascinated by what happens when two cultures with different worldviews clash. That’s what interested Schaeffer about it. Like St. Augustine’s book

Ah, but which secular worldview? And for that matter, which Christian worldview? See, Schaeffer and Colson were

Which leaves us no room for Christian diversity, for freedom in Christ, for letting each believer be fully persuaded in their own mind without condemning one another.

But primarily political conservatism. Which is why they don’t realize

Many Christians, many worldviews.

I’m a fan of author and Christian apologist C.S. Lewis. His day job was as a don of medieval English literature at Magdalen College, Oxford; and later the chair of medieval and Renaissance literature at Magdalene College, Cambridge. For a while I was trying to track down everything he wrote, and wound up reading his final book, the literature textbook

The Discarded Image is about the “Medieval Model”—the worldview of western European Christians during the middle ages. He presented it as lectures to his students to explain how medievals viewed their universe. (Kinda important if you’re studying their literature.) But this worldview, the Christian worldview of its day, is a discarded image. Nobody believes it anymore.

Yet the Medieval Model has all the qualities today’s apologists claim have to be part of any worldview, and are a part of their Christian worldview. It’s complicated, but it’s consistent with the scriptures and with itself, and it’s harmonious. In many ways it’s superior to today’s “Christian worldview”: It found ways to harmonize the bible with ancient pagan philosophers like Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics. It had a view of the cosmos which captured the imagination and inspired creativity.

But it was wrong.

The bible parts were wildly misinterpreted. Too many of the blanks in Christian theology were filled in by pagan thinkers or opportunistic churchmen. The biology wasn’t scientific whatsoever; it’s laughable nowadays. The astronomy wasn’t scientific either.

The Medieval Model’s centerpiece was the Great Chain of Being, a cosmic totem pole which sorted out where every creature fit in God’s hierarchy. God’s on top, of course; bugs are on bottom, and humans are somewhere below angels and above animals. It clearly violates God’s idea of no ranks in Christ Jesus,

Y’see, the human brain has a knack for recognizing patterns. Even when no such patterns exist. The brain wants to make sense of the world, even when

Problem is,

The Discarded Image makes it obvious a worldview can be popular, yet entirely wrong. Even a Christian worldview. Especially a Christian worldview—because it presumes we have it, so therefore we’re right. And we’re not.

Likewise we have Christians who densely don’t recognize any other Christian worldviews. Like a member of the Christian Left, whose politics are more about social justice than social conservatism, whose economic views are more about equality and socialism than laissez-faire capitalism. You know, things which Jesus and the apostles never talked about—which means these things are optional for Christians of good conscience. But if these beliefs aren’t optional, believing otherwise

Christ Jesus is supposed to bridge these gaps in beliefs. He does, if we let him. But if we’re insistent we know how to think and behave, instead of leaving these convictions to the Holy Spirit, nothing’s getting bridged. We just have disunity.

Jesus’s view.

Jesus didn’t comment on every issue and problem in the world. He left a lot of blank spots. He left those for us to

The problem is when we take one of the blank spots and insist it’s not blank. There are no gray areas, we’ll claim; it’s black and white.

Religion’s a good example: We Christians have many traditions and practices which facilitate our relationship with Jesus. True, Jesus never invented half this stuff. He never instructed us to put crosses on our jewelry, or fishes on our cars. But he’s okay with them—when they remind us to follow him. He’s not okay with them when we cling to them instead of him, and our religion goes dead. When this happens, God often insists we step away from our dead religion, and go back

Same deal with worldviews: When a worldview helps us grow our relationships with Jesus, good! When it doesn’t, or offers

I’m a trained theologian. I can tell you what Jesus thinks about the issues he actually did discuss in bible. The rest, I don’t know how he thinks. I don’t know what he thinks of the separation of church and state, of same-sex marriage,

So this is why I don’t claim to have, or follow, or especially defend, “the Christian worldview.” Like Paul, I don’t claim I’ve arrived. Instead, I claim I’m rubbish, and put aside my junk in order to follow Jesus, and cling to what I know he actually taught.