The English-language bible of William Shakespeare, of John Bunyan, of John Donne, of the first colonists who founded the future American states—namely the pilgrim fathers who traveled aboard the Mayflower and founded Plymouth and Massachusetts—was not

And some of it doesn’t. Despite the publication of the

It’s called

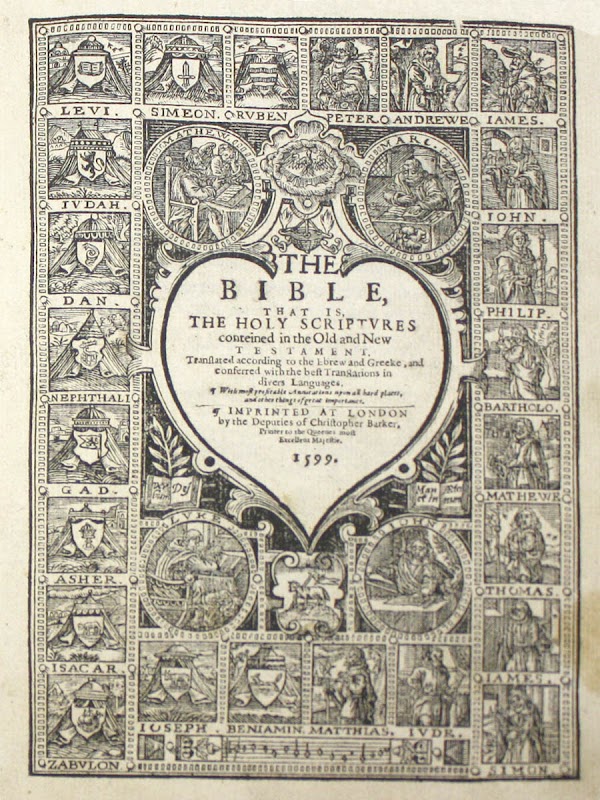

A Geneva Bible title page, published in London by John Barker in “1599.” That’s the date Barker put on all Geneva Bibles published after King James banned their production in 1611. Houston Baptist University

Tudor was a Roman Catholic. In part for political reasons, since her legitimacy as queen was based on it; in part for personal reasons, as she had been convinced by her Catholic family members she had to save England from the “heresy” of Protestantism. So Tudor started persecuting Protestants, particularly Protestants who had dared to translate the bible into English without Catholic permission. The persecution began with John Rogers, who had dared to revise the Tyndale Bible; he was burned to death in 1555. Protestant scholars decided it was safest to go into exile in a good Protestant country.

Since most educated Englishmen spoke French, where better than a French-speaking country? And since many of ’em were

There were English-language bibles at the time, but not good ones. John Wycliffe's bible was only partially complete, and many Protestants still considered him heretic. William Tyndale made a pretty good translation of the New Testament, but he was also considered heretic, and executed for it in 1535. Myles Coverdale, who was neither a Greek nor Hebrew scholar, borrowed Tyndale’s NT, cobbled together an Old Testament from German bibles and

So since these refugees had time—and the resources of a whole lot of Protestant scholars who’d moved to Geneva under persecution—they decided to tackle a new bible.

The team who produced the bible.

Myles Coverdale had fled to Geneva with the rest of them, but it’s unlikely he had anything to do with the Geneva Bible. Like I said, he wasn’t a biblical languages scholar. But one of the notables who was there at the time was Robert Estienne, who was developing the then-current edition of

William Whittingham, a polyglot Oxford student who later became John Calvin’s brother-in-law, started the ball rolling by publishing his English translation of the New Testament in 1557. He then put a team together to help him produce the entire bible; he concentrated on revising and improving his NT, while Hebrew scholar Anthony Gilby oversaw the Old Testament. These men had plenty of help from English scholars Christopher Goodman, a divinity professor; Thomas Sampson, a lawyer; and William Cole, a clergyman.

Instead of going with the traditional Latin renderings of Old Testament names, the translators tried to

Mary died in 1558, and was succeeded by succeeded by her Protestant sister Elizabeth (as Queen Elizabeth 1, 1558–1603). It meant the English exiles could return… but the translators chose to stick around and finish their bible. John Bodley published it in Geneva in 1560, and it included a dedication to the new Queen Elizabeth. (The spelling has been updated, ’cause we standardized it in the 1700s):

To the most virtuous and noble Queen Elizabeth, Queen of England, France, and Ireland, etc. Your humble subjects of the English church at Geneva, wish grace and peace from God the Father through Christ Jesus our Lord.

Followed by a few pages of sucking up, as medievals tended to do to kings; comparing her to Zerubbabel who rebuilt the temple, and suggesting she put good Protestants in government jobs so they could “minister justice according to the word.”

Copies made their way to England and Scotland. Took a few years before the Geneva Bible was published there; the New Testament was finally published in 1575, and the whole bible the next year. But in Scotland it became huge. Church of Scotland founder John Knox, who had been in Geneva while the bible was produced, petitioned his king, James Stuart (reigning as King James 6, 1567-1625) to publish it, which he did in 1579—thus making the Geneva Bible the first bible published in Scotland.

More than that: Stuart required every household who could afford it, to buy one.

The Geneva Bible, opened to

Why it was a big deal.

Humanity’s first printed bibles were huge. It is

The Geneva Bible, by contrast, was produced for the public. For individual, ordinary Christians. In ordinary, easily legible, Roman type.

Its dimensions were usually 5½ by 8½ inches (14 × 22cm), although sometimes twice that size for churches, and half that size for even more portability. In Scotland the price was fixed by law at 4 pounds, 13 shillings, 6 pence; that’s about $100 in today’s money, and at the time was less than an average week’s wages, which just about everyone could scrape together. Devout people especially.

It was the first bible to use verse numbers, and the first to use italics to indicate which words had to be added to the English text for clarity.

Unlike big giant church bibles, the Geneva Bible didn’t only contain the biblical text. It was the first English-language study bible. It has notes. If you couldn’t quite tell what a verse meant—or whether it was to be

There were maps. Illustrations. Cross-references. Footnotes. What biblical names meant. A glossary. A bible timeline.

If you didn’t know anything about the bible and its history, you now had a bible which could get you up to speed about all these things. All you had to do was get literate—and if you were a devout Christian, now you had a very good reason to learn to read.

The Geneva Bible at

The commentary was written by Laurence Tomson. He updated it twice: In the 1576 edition, he included Pierre L’Oiseleur’s notes on the gospels from the 1565 edition of Theodore Beza’s Greek/Latin Bible (which L’Oiseleur himself cribbed from Joachim Camerarius’s History of Jesus Christ). In the 1599 edition, he added Franciscus Junius’s notes on Revelation, replacing the original notes taken from John Bale and Heinrich Bullinger.

The notes as a whole made a massive impact on British Protestantism. It introduced them to Protestant theology, Calvinism in particular. It furthered the

And another thing the notes taught, which had a big impact on British politics in the 1640s, was that the king is not above the Law. (It taught that because the bible teaches that.) Whenever kings descended into tyranny, the notes rightly objected. This became a great irritant to James Stuart of Scotland, who grew up in France and was a huge fan of their style of absolute monarchy. But largely thanks to the Geneva Bible, the Scots and English grew to reject the divine right of kings… paving the way for the Second Civil War, the overthrow and execution of Charles Stuart, and in the next century, the American Revolution.

Seventy editions of the Geneva Bible were published during Elizabeth Tudor’s reign. The Geneva Bible became the bible—the usual household bible of English-speaking Protestants. The reason so few of those old copies exist today? People wore them out. They read them to tatters.

When Elizabeth Tudor died in 1603, her cousin James Stuart inherited the throne of England, and combined his two kingdoms of Scotland and England, creating the United Kingdom. As the new head of the Church of England, Stuart called for the publication of

Puritans didn’t trust the new King James bible (for good reason), so demand for Geneva Bibles continued. They’d ship ’em in from Switzerland and the Netherlands if possible. But they didn’t need to: Robert Barker, who published King James Versions for the government, quietly kept publishing Geneva Bibles on the sly, marking their title page with “1599” instead of the actual year of publication. Puritans kept right on buying and using the Geneva Bible instead of the

The Geneva Bible turned Britain into a biblically literate island and culture. Not that it necessarily made ’em any more Christian. Puritans, trying to activate the millennium, got too politically-minded… and overthrew the king, passed overly strict laws, and basically alienated people as they sought earthly perfection instead of

Iffy politics and theology aside, I still find the Geneva Bible to be a really impressive undertaking, which is why I like to share its history.