- TRIBULATION tri.bu.la.tion noun. Great suffering.

- 2. The cause of great suffering.

- 3. An End Times period of suffering around the time of Jesus’s second coming.

- [Tribulational tri.bu.la.tion.al adjective.]

Tribulation is an old-timey word which, to many people and Evangelicals in particular, has to do with the End Times. Hence writers find it useful: You wanna talk about suffering, but wanna make it sound like really awful suffering, as bad as suffering can be? You call it tribulation.

Thing is, when “tribulation” comes up in the King James Version, it means any and every kind of suffering. Not just the worst-case-ever kind of suffering. I mean it is used to describe that, Mt 24.21 but it’s used for all the other kinds. ’Cause suffering is part of the world we live in.

- John 16.33 KJV

- These things I have spoken unto you, that in me ye might have peace. In the world ye shall have tribulation: but be of good cheer; I have overcome the world.

Life is suffering. But Jesus has conquered the world.

So when we read of tribulation in the scriptures, it’s interchangeable with suffering. Don’t go reading great suffering into it… unless the context shows you oughta. ’Cause sometimes you oughta.

But most of the time it’s just life. And Christians shouldn’t be so surprised and outraged when life happens to have suffering in it. Problem is, we do. In the United States, Christians live very comfortably. Hence many of us are under the delusion that once we came to Jesus, our sufferings were over. Totally over. Erased by Jesus.

So whenever suffering does happen to an American Christian—or really anybody who lives in a first-world country with religious freedom and a comfortable Christian majority—we don’t assume it’s part of the usual suffering found in our fallen world. We assume it’s an aberration. Something lowered Jesus’s hedge of protection and let suffering in. Probably for one of these reasons:

- The devil’s trying to rip us a new one like it did Job, and for whatever reason God’s allowing it.

- We sinned, or otherwise stepped outside of God’s perfect will. God himself is out to smite us.

- We didn’t sin—but to preemptively keep us from sinning, or build character, God’s smiting us anyway. Like he did Paul. 2Co 12.7

- Somebody cursed us. So we need some form of supernatural deliverance; something to get the evil spirits to bug off.

- The End has come. Or at least it’s a sign of the End, a warning of the End, a glimpse of End-Times-style judgment, or something related to all that.

Generally we go for worst-case scenarios. We never consider the very real likelihood our suffering doesn’t mean anything. We insist it has to mean something; everything means something. We’re just that important. (Or narcissistic.)

Nope. Reality doesn’t work like that. Christianity doesn’t either. Jesus never guaranteed a trouble-free existence in this age. Read that John verse again: “In the world ye shall have tribulation.” There will be tribulation, and Christians aren’t exempt. In fact we should expect pushback when we follow Jesus properly. Not even our homes are safe.

- Matthew 10.34-36 KJV

- 34 Think not that I am come to send peace on earth: I came not to send peace, but a sword. 35 For I am come to set a man at variance against his father, and the daughter against her mother, and the daughter in law against her mother in law. 36 And a man’s foes shall be they of his own household.

Face it: The road to God’s kingdom has a fair amount of tribulation on it. Ac 14.22 Every antichrist is gonna want to pick a fight. Every hardship is gonna be waved around as if it’s proof God’s not around or doesn’t care. Even fellow Christians are gonna test our commitment to Jesus when times get rough—partly because they insist times should never get rough, and partly because they wanna blame somebody else for their suffering; and here’s where they start to pick on all the sinners in the world. Challenge them for their gracelessness, and watch ’em turn on you.

And I haven’t even yet got to the great tribulation.

The “great tribulation.”

According to Darbyists—plus all the pagans who borrow Darbyist ideas to write their pop-culture versions of the End—there’s gonna be a profoundly awful period of human suffering right at the very end of history. Right before Jesus returns to either put it to an end, or (according to dark Christians) add to it by destroying everyone they he doesn’t like.

The idea comes from this statement of Jesus’s:

- Mark 13.19-20 KJV

- 19 For in those days shall be affliction, such as was not from the beginning of the creation which God created unto this time, neither shall be. 20 And except that the Lord had shortened those days, no flesh should be saved: but for the elect’s sake, whom he hath chosen, he hath shortened the days.

The KJV calls it affliction, but Darbyists go with “great tribulation.” They describe it as the seven-year period between the secret rapture, when all the Christians get magically whisked to heaven before the really bad stuff happens, and Jesus’s second coming. During this time the Beast is expected to take over the earth and make it awful, particularly for Christians.

Wait, how’s the Beast gonna make life suck for Christians when we were all raptured?—because the scriptures do describe the Beast fighting and defeating saints. Rv 13.7 Well, Darbyists imagine two possibilities: Either the rapture happens in the middle of great tribulation, which means Christians only suffer in the first half; or they figure some pagans who were “left behind” in the rapture must’ve repented, became Christian, and now have to live through great tribulation.

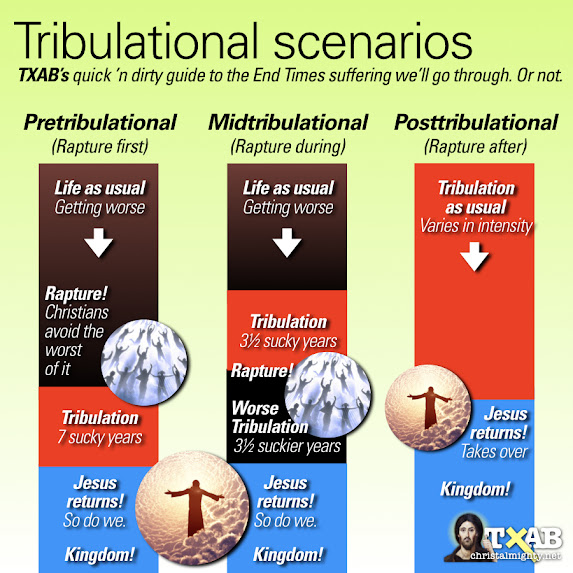

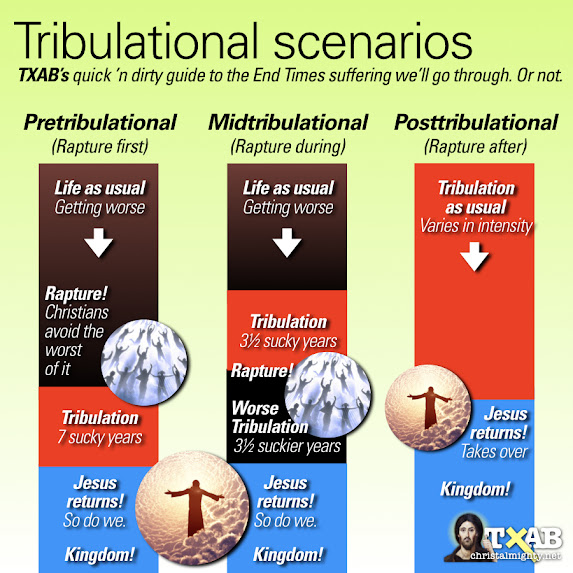

Hence we have three tribulational scenarios, all named after where the rapture takes place in relation to great tribulation.

- PRETRIB The pretribulational belief is we get raptured before any great tribulation happens. (John Hagee preaches this idea.)

- MIDTRIB. The midtribulational belief is we go through some great tribulation, but Jesus raptures us before the really really bad stuff takes place. (Jim Bakker promotes this idea, and really wants to sell you stuff for your End Times bunker.)

- POSTTRIB. The posttribulational belief is we’re already going through tribulation. And Jesus raptures us at his second coming.

For visual learners, I got an infographic.

Three timelines for the very last days before Jesus’s return.

As I said in my article on the rapture, there is no secret rapture in the bible. The rapture is far from secret: It happens when Jesus returns, with a black sky and trumpet blast and in full view of everyone. So where do Darbyists get the idea there’s a secret rapture either before or in the middle of tribulation?

Largely it’s futurism, their belief every End Times event happens in the future. John Nelson Darby was a cessationist who believed God turned off the miracles. But all the End Times visions are full of miracles, so Darbyists figure they can’t possibly take place in the miracle-free present day. Nor in any of the days since the bible’s completion. Everything must therefore happen in our future. Beginning with a secret rapture, based on various verses they take out of context to support both Darbyism and their various wish-fulfillment ideas like not suffering.

True there are some Darbyists, like Tim LaHaye, who figured some miraculous events take place leading up to the secret rapture. That’s because LaHaye was continuationist: He didn’t believe God turned off his miracles. Yet he was still Darbyist. How? Simple: LaHaye grew up Darbyist, and never thought to question the whole screwy system. He assumed it was valid, because everybody he knew treated it as valid. Lots of continuationists share this same defective boat. That’s why they’re all wet.

The historical great tribulation.

Because great tribulation must occur in the future, Darbyists tend to downplay, if not be utterly clueless about, a period of great tribulation which entirely fulfilled Jesus’s prophecy about the destruction of Jerusalem. It’s when the Romans destroyed it in the year 70, fulfilling this statement of Jesus’s:

- Mark 13.30 KJV

- Verily I say unto you, that this generation shall not pass, till all these things be done.

This happened four decades after Jesus predicted Jerusalem and the temple’s destruction—within the lifetime of that generation of listeners. Mt 24.34, Lk 21.32 Flavius Josephus, who personally saw it, described it like so. (William Whiston’s translation.)

Now the number of those that were carried captive, during this whole war, was collected to be 97,000. As was the number of those that perished during the whole siege 1,100,000. The greater part of whom were indeed of the same nation [i.e. also Jews], but not belonging to the city itself. For they were come up from all the country to the Feast of Unleavened Bread; and were on a sudden shut up by an army; which at the very first occasioned so great a straitness among them, that there came a pestilential destruction upon them; and soon afterward such a famine, as destroyed them more suddenly.

And that this city could contain so many people in it, is manifest by that number of them, which was taken under Cestius. Who, being desirous of informing Nero of the power of the city, who otherwise was disposed to contemn that nation, intreated the high priests, if the thing were possible, to take the number of their whole multitude. So these high priests, upon the coming of that feast which is called the Passover, when they slay their sacrifices, from the ninth hour till the 11th; but so that a company not less than 10, belong to every sacrifice: (for ’tis not lawful for them to feast singly by themselves). And many of us are 20 in a company. Now the number of sacrifices was 256,500; which, upon the allowance of no more than 10 that feast together, amounts to 2,700,200 persons that were pure and holy. For as to those that have the leprosy, or the gonorrhea; or women that have their monthly courses, or such as are otherwise polluted, it is not lawful for them to be partakers of this sacrifice. Nor indeed for any foreigners neither, who come hither to worship.

Now this vast multitude is indeed collected out of remote places. But the entire nation was now shut up by fate, as in prison; and the Roman army encompassed the city when it was crowded with inhabitants. Accordingly the multitude of those that therein perished exceeded all the destructions that either men or God ever brought upon the world. For, to speak only of what was publicly known, the Romans slew some of them; some they carried captives; and others they made a search for underground: and when they found where they were, they broke up the ground, and slew all they met with.

There were also found slain there above 2,000 persons; partly by their own hands, and partly by one another, but chiefly destroyed by the famine. But then, the ill savor of the dead bodies was most offensive to those that light upon them. Insomuch that some were obliged to get away immediately; while others were so greedy of gain, that they would go in among the dead bodies that lay on heaps, and tread upon them. For a great deal of treasure was found in these caverns; and the hope of gain made every way of getting it to be esteemed lawful.

Many also of those that had been put in prison by the tyrants were now brought out. For they did not leave off their barbarous cruelty at the very last. Yet did God avenge himself upon them both, in a manner agreeable to justice. […] And now the Romans set fire to the extreme parts of the city, and burnt them down, and entirely demolished its walls. Jewish War 6.9.3-4

Josephus’s line, “The multitude of those that therein perished exceeded all the destructions that either men or God ever brought upon the world” sounds pretty much like Jesus’s, “For in those days shall be affliction, such as was not from the beginning of the creation which God created unto this time, neither shall be.” Yeah, humanity’s done worse since. The Holocaust of World War 2 immediately comes to mind. But for ancient times, when there were maybe 200 million people on earth, the destruction of a million-plus Jews is a profoundly significant disaster.

But to Darbyists, it’s not a castrophe; it’s an inconvenience. Some of the bible passages they claim are End Times prophecies, require a temple! But the Romans flattened it. Stupid Romans. Now somebody’s gotta rebuild the temple, otherwise their timeline won}t work: Great tribulation can’t effectively start, and Jesus can’t return.

How a new temple will get built without triggering World War 3 is questionable. Some Darbyists actually try to squeeze such a war into their End Times prognostications. Tim LaHaye’s novels simply stated a temple had been built already, and never say how.

Like I said, to them it’s an inconvenience. They don’t care about the death and suffering of millions of Jews when the Romans destroyed Jerusalem. They dismiss all of that as any potential fulfillment of Jesus’s warnings.

Seven years of tribulation.

The prophet Daniel had apocalyptic visions of the End. The LORD sent him the angel Gabriel to explain ’em… somewhat. Gabriel laid out a loose timeline for Daniel: Counting from Jerusalem’s reconstruction, Gabriel said there are only “70 sevens” till the end of time. Da 9.24 Most translations render this “70 weeks.”

- Seven sevens after Jerusalem is rebuilt, Messiah appears. Da 9.25

- Then 62 sevens of trouble. At the end of this, Messiah gets cut off, and an invading prince comes to make war. Da 9.26

- Then the last seven of history: The prince runs roughshod over Jerusalem till someone puts a stop to him. Da 9.27

In Revelation, Jesus gave John similar visions. Because both Jesus and John had read Daniel, more than likely Jesus referred to the visions of Daniel from time to time. But Darbyists believe these aren’t merely references nor visions: This part, they choose to take literally. Even though we should know better than to take apocalypses literally. The final seven of history, Darbyists insist, means a literal seven years. Seven years of tribulation.

What evidence do they have for predicting it’s literally seven years? None.

’Cause let’s apply their literalness to Gabriel’s sevens. Yep, that means we gotta do math. (Yikes.) Jerusalem was rebuilt in 515BC and Jesus’s life on earth, birth to rapture, was 7BC to 33CE. So from Jerusalem’s reconstruction to Jesus’s life, we get between 521 and 547 years. Each unit of Gabriel’s “seven sevens” can literally represent between 10.62 and 11.16 years. For convenience we’ll round it to 11.

Do I sound ridiculously literal? Absolutely I do. But Darbyists are worse.

Now that we’ve solved for x, let’s see about the next 62 sevens of history: If each unit is a literal 11 years, each seven is 77 years long, and 62 sevens is 4,774 years long. The last seven of history?—the “seven” of the great tribulation? It should literally be 77 years long. And if Jesus isn’t returning till the end of it, expect him round the year 4850. What, you thought he was returning sooner?

I’ve already gone way farther than Darbyists will. Because any interpretation of the End which pushes the End that far into the future, they consider unacceptable. They’re quite fond of saying the rapture can happen any second. They may fight one another over all the stuff which “has to happen first,” but generally they agree the End can begin any time. So every once in a while one of ’em does the math, realizes the math really doesn’t get ’em where they want to go… and dismisses the math. But they’ll definitely stick to seven literal years of tribulation.

Since literalness is the wrong way to interpret Daniel, what’s the correct way? Simple: Gabriel wasn’t presenting a timeline. Just a sequence. First Jerusalem gets rebuilt. Messiah comes. Much, much later the End comes—in chaos. How much chaos? Dunno; but every time “the day of the LORD” is described in the Old Testament there’s chaos. Mainly ’cause plenty of people don’t want the day of the LORD to happen, and are gonna object loudly. It’ll come just the same.

A “seven” doesn’t represent a time period, but an idea. Namely the time it took God to create heavens and earth, then rest. Throughout the bible, seven represents the time it takes to get something well and truly and perfectly done. Stuff gets finished within a seven, same as God finishing creation in a week.

So the seven sevens till Messiah: The Hebrew language repeats itself for emphasis, and seven sevens means something’s totally finished. It represents the fullness of time when God sent his Son. Ga 4.4 Not the literal five centuries before Jesus, and no, you don’t divide these years by 49 to figure out how long a “cosmic day” is. (And then ditch these cosmic days when it comes to how long the final seven lasts.)

Seven years of tribulation is entirely based on convenience. Darbyists don’t wanna suffer for 77 years. (Who would?) They want it to be relatively, reasonably short. Enough time to cram their prophecies into—since they won’t accept the idea they were fulfilled over the past 20 centuries of Christian history. Seven literal years works for them.

The Beast gets to run amok for the final 3½ years of it, ’cause Revelation says it was given power to do its thing for “42 months” before Jesus overthrows it. Rv 15.5 Nope, these 42 months aren’t “cosmic months” where every month represents a literal year (even though it’d fit the 77-year tribulation scheme mighty well). Gabriel notwithstanding, Darbyists insist these are literal months.

Well. You see the vast inconsistency throughout Darbyist interpretation schemes. I hope it convinces you to ignore all their other prognostications. They’re not at all reliable.

Will there be End Times chaos? Sure. Will it be a period of unimaginable suffering, worse than it’s ever been? No; that happened already. All the suffering in Revelation can be linked to historical events. We’ve had plagues which killed more people than we see in the apocalypses. Persecutions which decimated Christians. Beasts aplenty.

What happens when we demand tribulation last seven literal years? Date-setting.

In the final Left Behind novel, Glorious Appearing, every Christian in the book knows precisely when Jesus is gonna return. Not the precise time, but the day itself. ’Cause they’re Darbyists, and they know Jesus will return seven years to the day after the secret rapture. And in the book, he does!

In real life, Jesus said nobody, not even he, knows the specific day. Mk 13.32 He’s not obligated to any of our timelines. For they aren’t his timelines. He doesn’t set one, and it’s not for us to make one. Ac 1.7 Instead, trust that God has that in hand, and go preach the good news: Jesus is coming back. But to save the world—not scorch it with tribulation first.