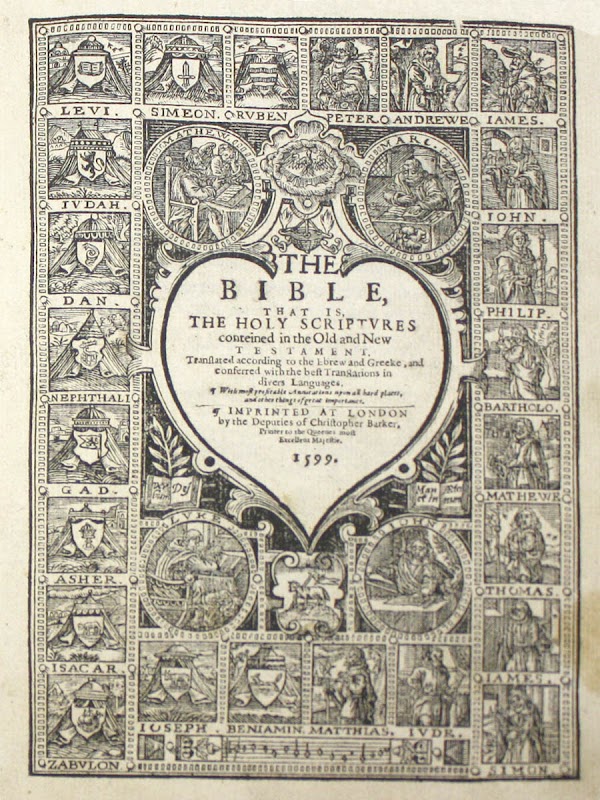

No doubt you’ve heard of the King James Version. But KJV fans and worshipers tend to be oblivious to the fact there were other English-language translations of the bible in that day. The KJV was one of many.

The KJV came out ahead of the pack, not because it was better than the rest—it was just as good as the rest—but because James Stuart, king of Scotland and England, suppressed the other existing translations… for political reasons. Y’see the Geneva Bible—the most popular translation of the day, the bible of William Shakespeare and the Pilgrims of Plymouth Rock—flat-out said in its notes Christians should resist tyrants. Unwelcome words to Stuart, who grew up in France and kinda coveted the French kings’ absolute dictatorships. Stuart’s son Charles was later overthrown and beheaded by Parliament for trying to create that kind of monarchy.

The KJV is debatably an improvement on its predecessors—the Tyndale Bible, Matthew’s Bible, the Bishops Bible, and the Geneva Bible among them. But KJV fans take it as a given these were inferior bibles, and haven’t a clue how good and valuable a bible the Geneva Bible was in its day. Usually because they’ve never even heard of it. Many KJV fans like Jack T. Chick like to pretend it never existed. The KJV fans never looked into its history, never took a peek at the previous English translations, and just assumed newer must mean better… until we start talking about present-day translations, and then suddenly newer isn’t better.

Naturally KJV fans know nothing about the KJV’s English-language successors. At least not till the 1881 Revised Version (adapted for the United States as the 1901 American Standard Version), which again, fans dismiss as irrelevant because it doesn’t base the New Testament on the Textus Receptus; as if the KJV translators bothered to look at the Textus most of the time; and as if they actually know why the Textus would be better than current Greek bibles. (It’s not, though.)

Usually they also don’t know about the KJV’s own revisions. They all know it was published in 1611; they don’t know the translators made more than 300 corrections to the text before its second printing in 1613. And that doesn’t even count the spelling. Spelling wasn’t standardized yet, so anyone could spell anything any which way, so long that people understood what they meant. So silent letters got dropped (“owne” became “own,” or “diddest” became “didst,” or “goe” became “go”) and minor grammatical and verbal changes were made (“you” became “ye” 82 times, “lift” became “lifted” 51 times, and so forth; “cheweth cud” became “cheweth the cud,” Lv 11.3 or “reign therefore” became “therefore reign.” Ro 6.12).

Minor changes, but lots of people felt free to make minor changes thereafter. Noah Webster produced an edition of the KJV in 1833 which Americanized the spelling. C.I. Scofield’s 1909 reference bible replaces hundreds of words from the KJV with what Scofield felt were much better translations.

These changes kinda let us in on the biggest problem with the KJV: It’s written in old-timey English. Not just old-timey English from our point of view; it was old-timey for 1611. The KJV’s translators—as they say in their preface!—didn’t actually want to create a whole new translation; they only wanted to fix existing ones. They considered themselves part of the translation tradition which extended all the way back to William Tyndale in 1522. But they hadn’t adjusted for the way language evolved over that century. Only poets and Quakers were referring to one another as “thee” and “thou” anymore, yet the KJV is full of these out-of-date pronouns. Vocabulary and styles were changing. Bibles always need to be translated to fit the way people currently speak—not demand people first learn how people used to speak. That may be fine for literature classes, but sucks in evangelism.

The other issue back then was the discovery of new ancient manuscripts. The Textus Receptus, the Greek New Testament the early English translations were based on, is full of errors. (That’s on purpose. Its editors wanted to include every word found in every available Greek manuscript. So of course that’d include any errors which crept into any bibles over the past 15 centuries.) But in 1627, King Charles Stuart 1 was given the Codex Alexandrinus by St. Cyril Lucaris, patriarch of Alexandria—a near-complete parchment copy of the Septuagint and New Testament, dating from the 400s, although some traditions claim it was copied earlier. It went to the British Museum; it’s been there ever since; English and Scottish scholars had full access to it. Totally could fix all the errors the Textus had put in the KJV.

So when the Puritans under Oliver Cromwell took over England in 1649, Parliament eventually created a commission to work on updating the bible. Unfortunately nothing ever came of it. Why not? Cromwell expelled them in 1653 for not holding new elections. New bibles had to wait.

In the meanwhile, Puritans created paraphrases—bibles and New Testaments where they translated the KJV into present-day English. (With big long book titles, which is what people did back then.) Like John Dale’s Bible Explained in 1652. Or Henry Hammond’s A Paraphrase and Annotations upon All the Books of the New Testament, Briefly Explaining All the Difficult Places Thereof in 1675. Or Richard Baxter’s New Testament with Paraphrase and Notes in 1685. Or Daniel Whitby’s A Paraphrase and Commentary upon All the Epistles of the New Testament in 1700. Or the volumes of John Guyse’s The Practical Expositor, or an Exposition of the New Testament, in the Form of a Paraphrase, with Occasional Notes in 1739-52—which John Wesley later used for his 1755 Explanatory Notes on the New Testament.

I should point out these paraphrases aren’t like the Living Bible or The Voice, in which the writers take creative license with the text; nor like the 2015 Amplified Bible, in which they try to shoehorn popular Evangelical doctrines and beliefs into it. They weren’t really trying to create new bible versions. They were trying to interpret it for their readers. Like when an expositor is analyzing a new bible verse, and briefly puts it in her own words: She’s just trying to make it more understandable.